Answer these 5 questions to better manage personally identifiable information (PII) in research

My sister Kelsey was a teacher at the local elementary school. In 2020, our worlds collided when she was chosen to participate in a study run by my employer, an educational publishing company conducting research on COVID-19 and its effects on teachers and education. When she received the invite, Kelsey reached out to me, saying she was nervous about speaking to an unknown researcher, and feared she would say something wrong. I’d simply said, “Just tell the truth.”

A week later, I opened up the participant recordings to take notes, and there my sister was, in the Zoom window, nervously biting her nails as she looked off-screen. In her interview, Kelsey discussed the challenges faced by teachers, students, and their parents. For Kelsey, the most disheartening change was the lack of communication with her students; the only way to reach students who didn’t have internet access was to call their house. Often, there was no answer. I heard her voice break as she said, "I worry about my students, not seeing them every day. Not knowing how they are. We don’t have a lot. It’s hard, but you do the best you can with what you have."

At that moment, I saw her cry…and it was right then and there…it hit me. This wasn't only a research participant; this was my sister. As her older sister, I felt I had failed her. I worked at this company and encouraged her to participate in this interview, knowing she might have been in an exposed position with the researcher. I didn't ever want this video used for anything other than what she had agreed to…for UX Research.

I always thought of our research participants as real people, but from then on, it was visceral. I realized that, as a Research Ops professional, I could do better. Participants spend their valuable time with us and allow themselves to be vulnerable. In return, we must collaborate with our legal and data privacy experts to increase knowledge and awareness of data privacy, prepare our participants, and weave research privacy and ethics into every part of the process. That moment with my sister changed how I approach research ethics. It made me realize that protecting participants isn't just about following rules — it's about honoring their trust.

The lowdown on data privacy

The 2024 Cisco Consumer Privacy Survey revealed that most consumers (53 percent) are now aware of privacy laws, and informed consumers feel significantly more confident about protecting their data (81 percent versus 44 percent). Research participants are more informed than ever, so people who do research (PWDR) can no longer afford to be casual about data privacy — and with more rigorous regulations (and penalties) in place, companies can’t afford to be complacent either. However, if you don’t know a lot about data and privacy regulations, knowing where to start can feel daunting.

Even a simple internet search for “data privacy research guidelines” will take you down a rabbit hole large enough to swallow you whole. You’ll find thousands of articles littered with terminology and conflicting information. Data privacy is a constantly evolving and complex world. While the fundamental privacy principles established in the OECD's 1980 Guidelines continue to provide a foundation for global data protection laws (article behind a paywall), they have undergone formal revisions in 2013 and ongoing reinterpretation to address unprecedented challenges posed by AI, social media, and modern data processing technologies.

It can be a lot to take in, but you don’t have to do it alone. First, you must intentionally partner with your data privacy partners. Second, use the 2016 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), one of the strictest data privacy laws, as a baseline when implementing new research guidelines, because you'll naturally comply with the majority of global data privacy requirements. (While your research may not be global now, even in the US, new state laws have requirements similar to GDPR.)

PII is at the heart of data privacy

While data privacy covers a lot, one concept that's absolutely central to research is personally identifiable information, or PII. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, PII or personal data is defined as "information which can be used to distinguish or trace an individual's identity, either alone or when combined with other information that is linked or linkable to a specific individual." The easiest way to think about PII is this: if I search the internet, can the information identify this person?

A special category of personal data exists, known as sensitive data, which those in the health and finance industries should be especially aware of. Additional security is necessary because this information, if disclosed, could be abused and cause the participant severe harm, such as identity theft, financial fraud, and discrimination. In their article on the Cyphere blog, What Is Sensitive Personal Data? Examples and Data Protection (GDPR) context, Cybersecurity Consultant Harman Singh explains examples of sensitive data:

These examples fall under special category data, which requires extra security measures and specific lawful grounds for processing under the GDPR. Under the GDPR, (from Article 4(13), (14) and (15) and Article 9 and Recitals (51) to (56)), sensitive personal data is defined as personal data revealing or concerning an individual’s:

- Racial or ethnic origin: such as skin color, cultural background, or nationality.

- Political views, affiliations, or opinions: such as party membership or voting history.

- Religious or philosophical beliefs: such as their faith, spiritual practices, or moral convictions.

- Trade union membership or affiliation.

- Genetic data: inherited or acquired genetic characteristics obtained by analyzing a biological sample or other means.

- Biometric data for identification purposes: physical, physiological, or behavioral characteristics, such as fingerprints, facial recognition data, or iris scans.

- Health data: physical or mental health, including the provision of health care services, reveals information about their health status, medical history, or treatments.

- Data concerning a person’s sex life or sexual orientation: an individual’s sexual preferences, practices, or orientation.

While primary researchers will know participant identities, these identities must remain anonymous to anyone outside the immediate research team (see this article, “Anonymising Interview Data: Challenges and Compromise in Practice”). Maintaining PII confidentiality is crucial as it minimizes risks to your team and company, and reduces the potential for harm to your participants.

Understanding what constitutes PII and sensitive data is just the beginning. The real challenge is systematically managing this information throughout your research process. Without previous guidance, there is a high probability that PII could exist in every phase of research, from participant recruitment to your insights repository. It’s essential to define the research tasks that generate PII data, so you can not only remove unnecessary existing PII but also plan for the proper handling of PII in the future. That's where my framework comes in: The 5 Questions of PII.

The 5 questions of PII

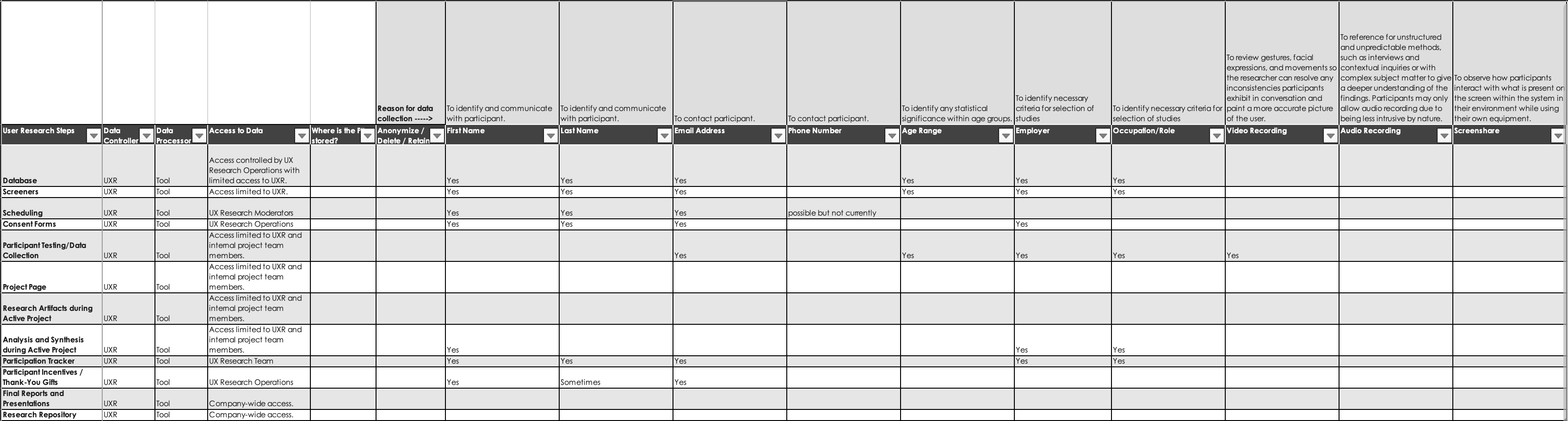

I created the 5 Questions of PII and its corresponding companion document, the ResearchOps PII Collection and Storage Template (see Figure 1), as a useful tool for remembering and sharing what PII is necessary to document. You may find it helpful to reference the document and its examples as you read through the 5 Questions of PII:

- WHO is the Data Controller and the Data Processor? Who will have access to the PII?

- WHAT PII will be collected? What data, when combined, equals PII?

- WHERE do you store PII?

- WHEN do you collect the PII? When will you delete or anonymize PII?

- WHY do you need this PII?

Who is the data controller? Who is the data processor? Who will have access to the PII?

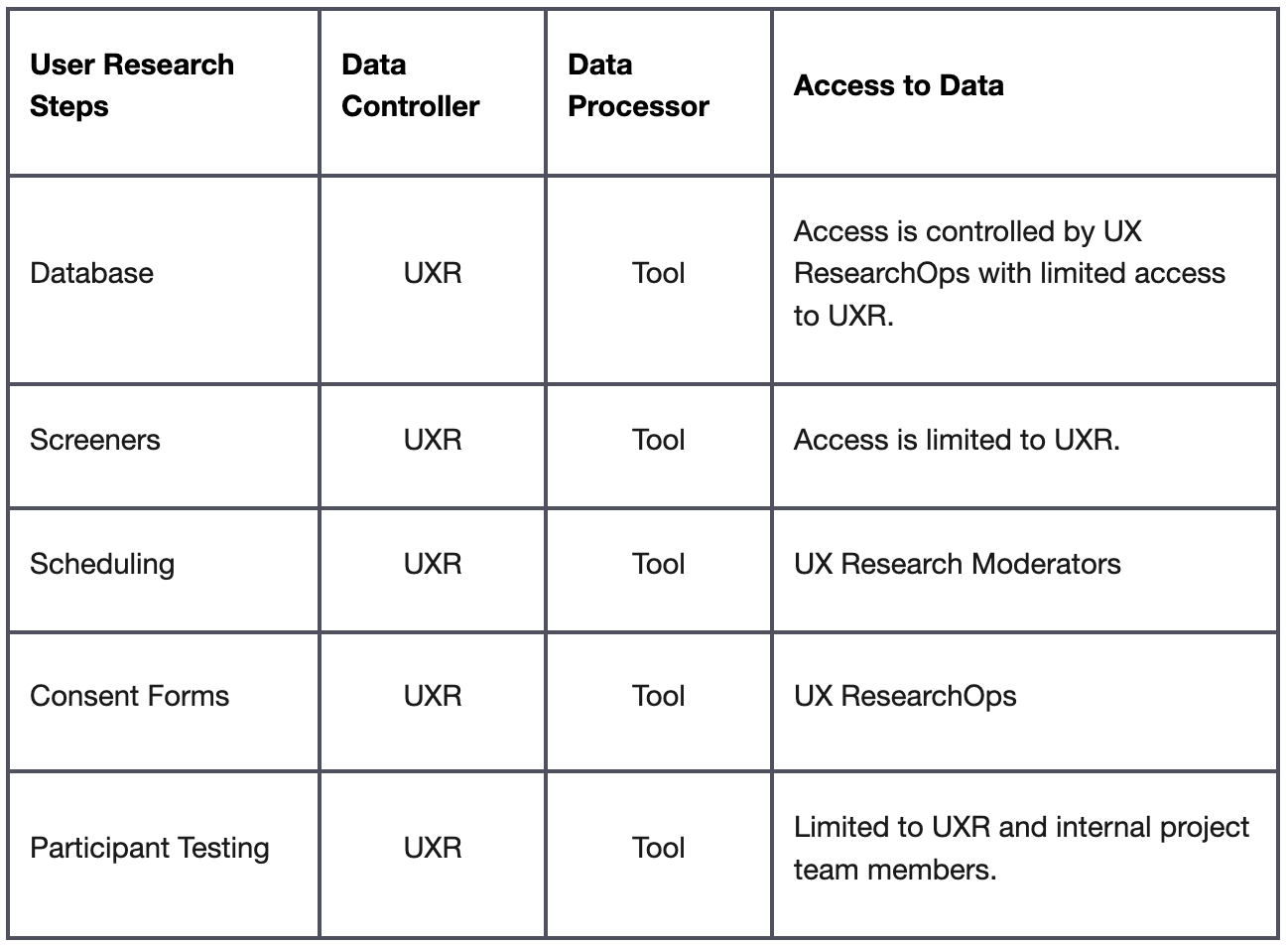

A data controller, such as an individual or company, is legally held accountable for securing data, ensuring transparency, and respecting people's rights. Data processors are not legally held accountable for their actions on the data controller’s behalf. This means that as research operations or PWDR, you bear the ultimate responsibility for ensuring your vendors and tools handle participant data appropriately — regardless of their compliance claims. Here’s how the roles of controller and processor are defined:

- Data controller: The person who decides how long you keep the data and what types of data you will use. It’s likely you or your team will be the data controller if you make these decisions.

- Data processor: Your tools and vendors typically act as data processors, while you remain the data controller who decides how to use their services.

For tool evaluations, while vendors may say they’re compliant with GDPR, their policies leave it up to the customers to decide what will be done with the data. So, the best practice is to ask vendors how personal data can be anonymized or deleted within their tools. Discuss with your data privacy teams if this is an adequate measure, and what additional follow-ups are needed. If anonymization is available through tools or services, verify that it works accurately and consistently and whether the process can be automated.

In terms of access, consider who will be involved in each task and whether they require personal data to complete it. Limit access to personal data to only those who need it. The best practices are as follows:

- If project members attend remote interview sessions as observers, create an invite separate from the moderator and participant so the observers’ and participants’ email addresses are not known to each other.

- If you have a data security contact, they can share information about how to secure data with the tools you use. For example, creating user groups that automatically update based on the reporting structure to be used in email, for access to file directories, etc.

Here's how to fill out Columns A-D (see Figure 2) in the ResearchOps PII Collection and Storage Template:

What PII will be collected? What data (when combined) equals PII?

Before launching any study, successful researchers ask themselves a fundamental question: What's the minimum amount of personal data needed to answer our research questions? This strategic approach not only protects participant privacy but also streamlines your data management processes. The key is to work backwards from your research goals to determine exactly what information is truly essential while minimizing participant privacy exposure. As you work backwards, identify what data collected could be classified as personal data, alone or when combined, such as full names, phone numbers, email addresses, employers, occupations, and audio, video or screen recordings.

Only collect the personal data you need during the study, then anonymize or delete the personal information that is unnecessary after completing analysis and synthesis. Once the data’s anonymized correctly, it’s no longer considered personal data. Take the following steps to ensure your data collection maps to your research goals:

- Review your problem statement. Is it clear what issue you want to address and why it matters?

- Review your research questions. Is it clear what you want to find out?

- Review the data that needs (or does not need) to be collected: What information or variables do you need for meaningful insight?

For example, in the study I mentioned about COVID-19 and its effects on K-12 education, here’s what I would outline:

- Review your problem statement. To inform our research, our participants needed to be K-12 teachers.

- Review your research questions. Due to the unknowns of COVID-19, many states had implemented lockdowns, and teachers had been redirected to remote learning. In order to learn remotely, you need access to the proper materials and technology. If they didn’t have access, how close were they to accessible technology and materials?

- Review the data that needs (or does not need) to be collected. What personal data wasn’t necessary at all? Participant age. What if we wanted to see if older teachers struggled with the technology they had never used before? Was this considered in the research questions? If not, this data could be shared by the participant without prompting and anonymized as an insight for future studies, but age wasn’t necessary to collect and consider when recruiting for this study.

Where do you store PII?

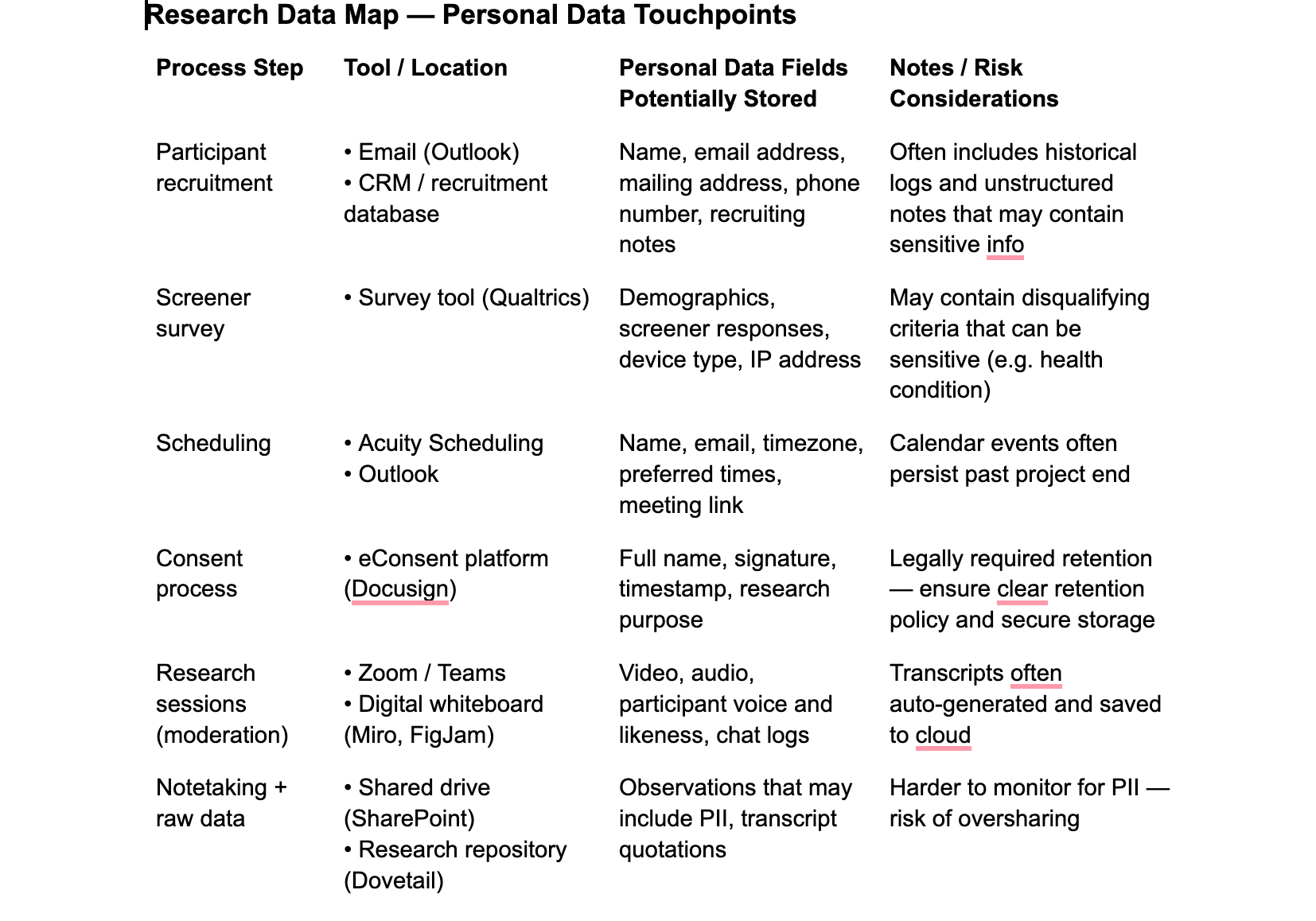

Does personal data exist in tools? Do you have personal data in your email? What about research databases, local drives, screeners, scheduling, consent forms, project pages, analysis and synthesis, participation, and incentive trackers?

To ensure best practices, run a workshop with PWDR to ask about their processes and where they store their information, then create a data map (see Figure 3). Start broad within the different stages of research, ask questions and invite discussions around why they do research or store research data in this way. Then, review the data, and craft potential suggestions for the ideal storage solution(s) and share with your partners. For example, you may identify the need to set up cross-functional guidelines around sharing specific data to reduce existing silos between teams while maintaining data integrity. If you notice once a study is over, there is a “set it and forget it” mindset, there would be clear benefits to establishing explicit policies for data retention, implementing data clean-up processes during the study wrap-up and scheduling routine audits to manage the growing storage and meet compliance requirements.

When do you collect the PII? When will you delete or anonymize PII?

Let’s say you're three months into a study on remote learning challenges. Sarah Mitchell from Riverside Elementary shared insights about technology gaps, while Michael Fletcher from Downtown Middle School discussed budget constraints. During recruitment and interviews, you needed their full names for scheduling and their school information for context. But now you're analyzing data — and this is where most researchers miss a crucial privacy opportunity. Strewn through your documents, you’ll find personal data everywhere — participant names in transcripts, school locations in notes, email addresses in correspondence, demographic details in surveys.

The key principle is simple: once you move from data collection to analysis, most personal identifiers become unnecessary. Personal information that was essential for building rapport during interviews becomes an unnecessary privacy risk once you've extracted the insights you need. Here's what this looks like in practice:

- Replace participant names with codes: Sarah Mitchell becomes “Participant 1” or “Teacher A.” Keep a secure participant register (limited access only) that links real names to aliases and retains essential contact information, like email addresses for future study invitations, while removing this information from all other research materials.

- Anonymize locations and identifying details: Change "Riverside Elementary" to "Rural K-5 school" — keeping only contextual details that matter for your research.

- Train your team and create guidelines: Ensure templates explain how to recognize when PII is no longer needed and how to anonymize different data types.

For example, in the remote learning study I mentioned, this is what should happen during the transition to analysis:

- Replace participant names with codes: Full names were necessary for scheduling interviews, but "Teacher 3" works just as well for analysis of technology challenges.

- Anonymize locations and identifying details: We needed to know "Downtown Middle School" during recruitment to understand the urban context, but "Urban middle school serving 400 students" provides the same analytical value without the privacy risk.

- Set review dates and check compliance: What personal data wasn't necessary to retain? Email addresses. Once interviews were complete and follow-up communication ended, these should be deleted from transcripts, notes, and other research materials — keeping them only in the participant register as previously mentioned. The insights about budget constraints don't require knowing how to contact Michael — only that he teaches at an under-resourced urban school.

Your data privacy experts can provide the company’s standard timeframe for retaining data, including whether researchers can request extensions if they have a logical reason. If extensions are allowed, work with your data privacy experts to identify necessary information to collect at the time of request, ideally through a form.

Why do you need this PII?

If you want to collect any data at all, you should be able to provide a reasonable explanation why the information is necessary to the research and how it will be used. If someone requests additional data simply “because it may be good to have in the future,” say no. Document the types of PII and related reasons for collecting these in Columns E-F, Rows 1-2 in the ResearchOps PII Collection and Storage Template to gather, for example:

- First Name: to identify and communicate with the participant.

- Email Address: to contact the participant.

- Occupation: to identify the necessary criteria for the selection of studies.

- Video Recording: to review gestures, facial expressions, and movements so the researcher can resolve any inconsistencies participants exhibit in conversation and paint a more accurate picture of the user.

- Screenshare Recording: to observe how participants interact with what is present on the screen within the system in their environment while using their own equipment.

You don’t know what you don’t know

This framework might seem overwhelming at first glance, especially when you're trying to apply it to your existing processes. Don't worry. I've got a practical approach to get you started. Think about what is still unknown, then set up an hour-long working session with your researchers. If uncertainty remains, set up some follow-up sessions to create alignment and clarity. Structure your first hour-long working session as follows:

- Spend five minutes at the beginning to set context and share what you want to accomplish.

- Process mapping should take about twenty-five minutes overall. Limit yourself to four or five key research stages or topics. As you go through each topic, take a few minutes to explain, then set a timer for five minutes and have everyone add stickies with their answers and any questions. Prompt your researchers about their processes, what data they collect at each step, and when/if it’s anonymized or deleted.

- During the next ten minutes, cluster the stickies into themes.

- Spend fifteen minutes encouraging discussions among the group to focus on where processes differ and identify best practices. Take notes in an area visible to the researchers with the findings, decisions, and any next steps.

- The last five minutes should include a quick summary of what you’ve learned. Thank the researchers for their time and invite them to continue adding more stickies if they think of others after the session concludes. As a final note, share a timeline for following up with next steps.

During these sessions, not only will you learn more about the existing PII and processes, but more importantly, you’ll have included your researchers in crafting data privacy goals and best practices—researchers who will now have a better understanding of data privacy concerns and potentially provide excellent perspectives. Once you've mapped out where PII lives, the next crucial step is partnering with legal and data privacy experts, who will know the ins and outs required. If you work at a smaller company, which may not have full-time legal and data privacy representatives, you’ll still likely have access to a general counsel from outside the company.

It’s the journey, not the destination

Building ethical research practices isn't a destination — it's an ongoing journey. Every small step you take along that journey makes research safer and more trustworthy for the people who generously share their time and experiences with us. If you find yourself spinning your wheels, start small — pull together researchers for an initial working session, gather relevant information to help guide early conversations — anything that might create momentum. Celebrate every win, with every step — big or small — as you travel along the path to produce ethical research that participants can trust.

Disclaimer: I’ve written this article from my perspective, research, and experience as a ResearchOps professional. I’m not a Legal or Data Privacy professional. This article is for informational purposes only and shouldn’t be considered legal advice.

Edited by Kate Towsey and Katel LeDu.

👉 The ResearchOps Review is the publication arm of the Cha Cha Club – a members' club for ResearchOps professionals. Subscribe for smart thinking and sharp writing, all laser-focused on Research Ops.

Rally’s Research Ops Platform enables you to do better research in less time. Find out how you can use Rally to empower your teams to talk to their users, without disjointed tooling and spreadsheets. Explore Rally now by setting up a demo.